From theSpec.com comes this post about workplace mental health concerns and how corporations may be in a better position to do something about it.

Here is a link to an executive summary of the report referenced in the above item.

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Business Can Lead the Way on Addressing Mental Health

Labels:

mental health,

workplace

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Wavelength

|

| http://sharetv.org/images/the_merv_griffin_show-show.jpg |

Long before he was a real estate tycoon and game show visionary, Griffin was a singer and, for a quarter of a century, he was a talk show host.

The show's format was similar to that of Carson's Tonight Show and he had many of the same guests; you just didn't have to stay up past 11:30 in order to see it.

We saw the show on a UHF station out of Burlington, Vermont. UHF was fascinating to us because, unlike the “regular channels” two through 12 that you selected with the rotary switch tuner that had hard, definitive stops for each channel, UHF was more of an interpretive spectrum and its stations were literally “tuned in” in the same way that you tuned in a radio.

I watched the show in the same way that an anthropologist watches a new culture: I most often had no idea what they were talking about, but I was captivated because these were adults talking to other adults about adult things. Perhaps, in some way, I was looking for a way to understand the adults in my world.

I have a few very clear memories of the show: the banter with trumpeter Jack Sheldon whose voice I recognized from the seminal “I'm Just a Bill” segment of Schoolhouse Rock; the regular appearances of Arthur Treacher, the British character actor who went on to lend his name to a chain of fish and chip shops; David Letterman appeared on the show early in his career as a stand-up and one of his jokes was “Hands up, everyone who's in the country illegally.” Mel Torme was on the show many times and I remember them talking about how he came to write “The Christmas Song” that Nat “King” Cole made unforgettable.

The genesis of that song is the stuff of legend now, but I can recall marveling at the disconnect between what they wrote and the circumstances that inspired it. It was the middle of summer and the hottest day of the year and Torme, with his writing partner Bob Wells, wrote the piece in an effort to imagine themselves into a cooler place.

As I have gotten older, I have come to the position that it is in the remembering that this time of year has its greatest power.

When you're a kid, the details of any given holiday season are a blur: it's uncomfortable clothes, strange foods, toys, visits to people you don't know, but who seem to know an awful lot about you. All that you want to do is play with your stuff, or depending on your age, the packaging it came in.

There is not a lot of nostalgia for this time of year when you're young. Like doctor's visits and exams, it comes around every year and the only thing that changes is the quality and variety of the gifts you receive.

Once you become an adult, once you break the annual cycle of holiday celebrations, you are driven to replace them with some sort of idealized facsimile.

Each of us I think goes through their first experience of this time of year as an adult when we are separated from family and familiars, from tradition and history. It can be a very disturbing, disorienting experience. It's like going from having your own room to staying in the guest room: nothing is where it is supposed to be and you are under some pressure to get up on time so the rest of the house can use the restroom. This is probably one of those foundational experiences that we all have to have in order to define ourselves as distinct from our families of origin.

And, as hard as it might be to experience, it is more difficult for parents when their children no longer come home for the holidays. It's one of those benchmarks that are as inevitable as they are unsettling. A corner has been turned when the annual holiday portrait can no longer be organized without benefit of negotiation and trips to the airport.

|

| http://ow.ly/82PU3 |

And yet every year we relaunch our efforts to turn our holiday fantasies into reality because we all want to do a good job. Long after we may have abandoned Santa Claus we still try to make it onto his list and avoid the lump of coal in our stockings.

Like so many of our traditions associated with Christmas, this high-stakes behavior modification has its roots in central Europe where more than just the weather is grey.

|

| http://ow.ly/82PTe |

To this day, we frame Christmas as a merit-based holiday where we expect to learn our place on the naughty-nice axis and be rewarded accordingly. If we are nice, we get a gift from St. Nick and if we are not, we get eaten. Even as adults, as the days get shorter, we alter our behavior in a kind of campaign for recognition and reward. Our self-worth is tied to the quantity and quality of the presents we receive.

Intellectually, we might know this is not true, but this risk-versus-reward idea is so ingrained that parents will question the love of their children if they are not able to provide the latest and the hottest gifts each year.

Celebrating the holidays is to hold oneself to an impossible standard: the tree is never big enough, the gifts are never exactly what was wanted and the meal was never good enough. Making matters worse are the seemingly endless array of self-appointed experts with tips and tricks on how to get the “perfect” this or the “ideal” that.

Lubricating the entire year-end celebration machine is a relentless musical soundtrack designed both to evoke and to provoke.

We are the the shoppers who “rush home with their treasures” so that we can get out “walking in a winter wonderland.” We buy chestnuts even though we don't have open fires. We commit to memory the names of the reindeer by humming the one about Rudolph and yet, when pressed can never come up with Comet, Donder, Cupid and Blitzen.

|

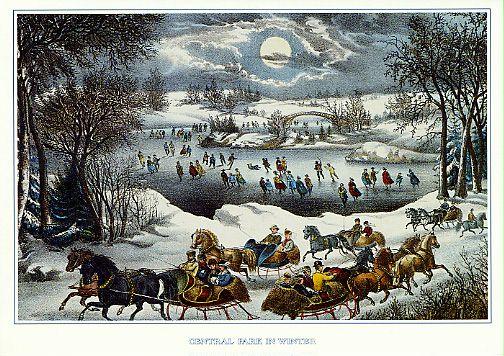

| http://ow.ly/82PXk |

I haven't quite figured out whether it's the music itself, or my associations to it, but every time I hear a cut from that recording I think of a warm fire, hot chocolate and many of the items from the “Most Wonderful Time of the Year” list. Most of all, I think of a time when Christmas was much less complicated.

In the days before the VCR it was always a challenge to figure out when the special would air each year and arrange our lives accordingly.

Even as a kid, I strongly identified with Charlie Brown and his struggle to come up with his own definition of Christmas.

It is a tribute to Schulz's artistry that, in just over twenty minutes, he and the animators are able to capture the complexity of Christmas. Each of the characters in the Peanuts universe speaks to some aspect of Charlie Brown's character. His eternal optimism comes from Linus, his ego from Lucy, his artistry and imagination from Schroeder and Snoopy, his self-worth from Pigpen. In the show, these and other characters literally dance around to their own music until Charlie Brown is able to direct them toward a coherent holiday celebration.

In the end, we are not presented with a simple answer: that this or that is the true reason for the season. Schulz uses Biblical language, but the real lesson is Charlie Brown's search for a meaning that makes sense to him, a personal vision.

Each of us has a spectrum of memories about this time of year. Each Christmas has a different character and each of those characters has its own music, or theme, and, like Charlie Brown, it is our responsibility to find a personal coherence. It's like the radio in that regard, you have to keep adjusting in order to stay on the proper wavelength.

--Graham Campbell

Associate Director

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)